By George R. Pilcher, The ChemQuest Group, Inc.

The 124-month recovery from the Great Recession officially peaked late in Q4 2019. Two short months later, in February of this year, the United States was plunged into a new recession as a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic and the concomitant mitigation tactics. Suddenly, everything changed—and not just with respect to the health of the populace. Economic, social, and business practices have also been upended. Essentially nothing has been left untouched, and—as we look ahead—very little is clear, other than the inevitability of permanent change.

In attempting to understand what life will be like in a post-COVID-19 world (hereinafter referred to as “COVID”), we all wish that we had crystal balls, but alas, we do not. As I submit this article in mid-June (with a few updates to the proof in July), I cannot help wondering how many of the particulars that I have covered might be altered, either by a little or a lot, by the time of its publication two months from now, in August. This is a caveat emptor for the reader, who is likely to know what, if anything, has changed its course since my “pen last touched paper,” and I hit “send” on my keyboard.

That said, it is doubtful that anyone other than the most committed optimist would predict anything better for 2020 than a global economy suffering from a minimum of a 4–7% decrease in gross domestic product (GDP), compared to 2019’s pre-COVID prediction of an increase of 2.9%, and even this generous assessment assumes that business will “return to usual,” on a global basis, beginning in Q3. If the recovery is not in full flood until Q4, the decline in global GDP rather quickly begins to approach an estimated 6.0–12.0%. As of June 24, the International Monetary Fund, anticipating a kick-start during Q3, indicated that the global economy will drop 4.9% (down from –3% forecast in April) for 2020: Asia-Pacific (APAC) will remain virtually unchanged, but individual countries in APAC will vary significantly—China will expand by 1.0%, but Japan will undergo a 5.8% contraction; the U.S. will decline by 8.0% and the EU by 10.2%.

Somewhere among the divergent scenarios being floated by an abundance of individuals and organizations about the likely economic effects of COVID is one that I personally consider to be the most probable, and which The Economist has christened “The 90% Economy.”1 At first blush, this may sound undesirable, but not necessarily disastrous. After all, flip it, and it means that the economy is only down 10%, and individual companies think nothing of enacting a “10% downsizing.” How bad can that be? The answer is: Really bad. Just how bad can be illustrated by looking at the two most calamitous economic events of the past 100 years: The Great Depression and The Great Recession. “Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide GDP fell by an estimated 15%. By comparison, worldwide GDP fell by less than 1% from 2008 to 2009 during the Great Recession.”2 Let that sink in for a moment—the most positive outcome currently being predicted for the global economy in 2020 is a 4.9% contraction of GDP in 2020, compared to a contraction of ≤ 1% for the Great Recession.

A New Normal

Just as the world experienced a “New Normal” following the Great Recession of 2008–2009, there will be a New Normal in the post-COVID era, and it is not going to represent “business as usual,” as defined by 2019. To help place this in a proper context, consider that China began emerging from lockdown in February of this year, significantly ahead of Europe and North America, and business appears to have returned to “normal.” Appearances can be deceiving, however:

Depending upon the source, the Chinese economy shrank somewhere between 6.8–8.6% year-over-year (YoY) in Q1 of 2020, following 6% growth in Q4 of 2019. It is the first such GDP contraction since recordkeeping began in 1992.3

In April, consumer spending in China was reported to be down by 7.5% YoY from 2019, which was better than the 16–19% decline reported for March,4 but still a millstone around the neck of the economy.

China’s hotel business was down nearly 70% in mid-Q2, an improvement from –90% in mid-Q1. It is, of course, true that China was the first region to come out of lockdown, while other global regions were still coping with COVID. As a result, travel to China from other regions has understandably been limited. There is no reason, however, to assume that the situation will be any different in other global regions as they begin to open up.5

China’s official unemployment rate for Q1 was 5.9% (∼20MM people), but this does not include people in rural communities or the majority of the 290 million migrant workers who make up unskilled labor in trades, construction, manufacturing and other low-paying but vital activities. Once these are factored in, there could easily have been 80MM people (17–19%) unemployed in China by the end of Q2,6 a situation that might easily be mirrored in certain countries in the West, as well.

Bankruptcies are on the rise in China—approximately 247,000 Chinese companies declared bankruptcy in the first two months of 2020, and another 213,000 by the end of Q1.7

Contrasting this with the United States and Europe, what would a 90% economy mean, practically speaking?

A 10% decrease in the U.S. GDP would be worse than that experienced during the Great Recession—would, in fact, be the worst since the end of World War II.

In an Associated Press poll taken on May 20, Americans did not see the country returning anytime soon to a pre-COVID normal. Instead, Americans largely envisioned a protracted period of physical distancing, covered faces and intermittent quarantines ahead, perhaps until a vaccine is available.8

While the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) anticipates recovery to be on its way by 2021, it cautions that it could take as long as a decade for the U.S. economy to return to its pre-COVID status.

On April 20, small shops in Germany were permitted to re-open, but the customers stayed away. During the lockdown in Denmark, consumers cut spending by 29%,9 and it is estimated that Sweden, which did not lock down, experienced among the highest per-capita death rates and saw consumer business, including services, drop by at least 30%.10 By late April, commercial tenants had fallen behind in their rent payments, also by 30%. These are disastrous numbers for a Scandinavian country.

Countless firms, both small and large, are struggling to remain viable; many will be forced to either close their doors voluntarily or be thrown into bankruptcy, which will only add to people’s financial worries and increase their overall fear of the future. This fear is not going to end with the opening of the U.S. and European economies—if anything, it will become more intensified as the dominos that COVID set up begin to fall.

On April 29, in a letter to Boeing employees, CEO David Calhoun indicated that, “The pandemic is . . . delivering a body blow to our business—affecting airline customer demand, production continuity and supply chain stability. The demand for commercial airline travel has fallen off a cliff, with U.S. passenger volumes down more than 95% compared to last year.”11

On June 16, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) issued a press release indicating it estimates that commercial airlines are expected to post a loss of $84.3 billion in 2020 and that government financial relief will be necessary to save many airlines.12 Hardest hit will be Asia-Pacific, followed by Europe and North America.13

Public opinion research in the first week of June showed greater caution among travelers in returning to travel. Only 45% of travelers surveyed intend to return to the skies within a few months of the pandemic subsiding. A further 36% said that they would wait six months. That is a significant shift from April, when 61% said that they would return to travel within a few months of the pandemic subsiding, and 21% responded that they would wait about six months.14

Champagne corks were popping at Delta Airlines in early January of this year, in celebration of what was claimed to be the most successful year in the history of the company. Just a few months later, on May 10, The New York Times reported that Delta and the other major airlines in the United States were losing $350–$400MM per day as a result of a 94% drop in passenger traffic.15

The future for the airlines is expected to be even more troubled than is currently the case. It is likely to be 4–6 years before the airlines return to the skies with the same regularity as in 2019, and ongoing troubles initiated by the COVID epidemic are very likely to drive consolidation or bankruptcy among both small and large carriers.

2020 and Beyond: Significant Economic Influences

But what about the years following 2020? What about 2021 and 2022 and possibly beyond?

How well the easing of restrictions is accomplished—and is accepted by consumers—will have a huge impact on any given country’s economy. Unknown at the time of this writing is the probability, the morbidity/mortality and the timing of a significant “second wave” of COVID, as occurred with the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1920.

Fear will be a significant economic influencer for some period of time. This is likely to vary on a regional, national and cultural basis, but—at its best—it will tax the recovery of the respective economies.

The world anxiously awaits anti-viral drugs (Remdesivir and others still under development) and efficacious vaccines, although efficacy is by no means guaranteed. The production of pharmaceuticals is particularly complex, with an attenuated value chain that more often than not causes significant scale-up issues. Many different companies are typically involved in manufacturing the various components of a new drug; by and large, only the final manufacturing step is performed “in-house.” The logistical considerations are potentially staggering, regardless of reports from some of the more upbeat prognosticators. There are many economic and availability issues associated with supply chain logistics of pharmaceuticals, and rarely have they been more active or agonizingly apparent than during the global COVID pandemic, when many countries, including the United States, fully realized to what extent manufacturing depends on starting materials supplied by China, India and other APAC nations. This is also true for virtually every other chemically based industrial segment. Moreover, local toll producers will be needed for various steps of the manufacturing process—pharmaceutical synthesis cannot just be taught via Zoom; it typically takes skilled personnel weeks, even months, of living “out of a suitcase” to get the manufacturing processes for new drugs up and running, to the point where they can be left in the hands of regional producers.

Paint and coatings product development is similar to that of pharmaceuticals, in that it begins in laboratories with polymer synthesis and formulation with numerous materials followed by manufacturing scale-up, packaging and ultimately shipping to the consumer. Like pharmaceuticals, the coatings industry relies heavily on a variety of chemicals and chemical compounds that originate in APAC/India, and supply chain disruptions have either already arisen, or are very likely to do so during Q2/Q3, for a broad array of starting materials needed by U.S. manufacturers.

Even though many experts believe that it may be 2024 or longer before pre-COVID levels of employment are reached in the United States, we believe that the paint and coatings industry will be back to the pre-COVID level of activity sooner than the general economy—perhaps as early as 2022. The reasons why things will not “return to normal” by 2021, for either the general economy or the paint and coatings industry, are complex, but—if we visualize the overall situation as a set of dominos set on end, and then tip the first domino into the second—we can see how the “domino effect” will keep the “COVID effect” alive well long after the disease is no longer of immediate concern. A few of the many factors that prevent swift recovery include:

- Loss of skills due to workers, voluntarily or involuntarily, going to other sectors of the economy; not being rehired in the areas where they originally practiced those skills; and highly experienced baby boomers choosing—or being forced into—retirement

- Higher unemployment during the post-COVID era due to shuttered businesses and reduced demand for labor

- Short-term disruption of established networks

- Longer-term disintegration of networks

- Lower occupancy of office buildings due to changing attitudes about the use of home and virtual offices

- Decreasing construction rate of office and other commercial buildings in favor of less complex, increasingly in-demand warehouses and distribution centers built to accommodate increased on-line shopping, an existing trend that has been accelerated by “COVID confinement”

- Jobs lost by PRO painters to DIYers as a result of consumers, confined to home during the COVID period, embarking on some home repairs, including painting; the PRO share is already coming back as of mid-June, but it will be two or three years before it reaches pre-COVID levels

- Supply chain disruptions set in motion by COVID, which will play out during the post-COVID period

. . . We believe that the paint and coatings industry will be back to the pre-COVID level of activity sooner than the general economy . . .

The State of the U.S. Paint and Coatings Industry, 2019–2021f

Regarding the “State of the U.S. Paint and Coatings Industry,” it is always important to look at the macroeconomic picture that surrounds all businesses that depend upon the specialty chemical stream for their livelihood. While the manufacturing sector in the United States is only weakly correlated to GDP under normal circumstances, the relationship becomes more pronounced under conditions of extreme economic duress, such as the COVID crisis. According to the CBO, GDP in Q1 of 2020 was down 3.5% from Q4 of 2019, and per the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the Bureau of Economic Analysis on July 17, the latest estimate for real GDP growth (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in Q2 is a decline of 34.7%. This decrease was sufficient to reduce a country from full employment to as high as 15% unemployment. The outlook for GDP during the remainder of 2020 is not pretty: The CBO estimates that the year will end with an overall GDP contraction of ~6% compared to 2019 and is only expected to increase to 2.8% during calendar 2021. It is within this context that we now turn to the U.S. coatings industry performance during 2020 so far, and its anticipated performance during the remainder of the year and into 2021.

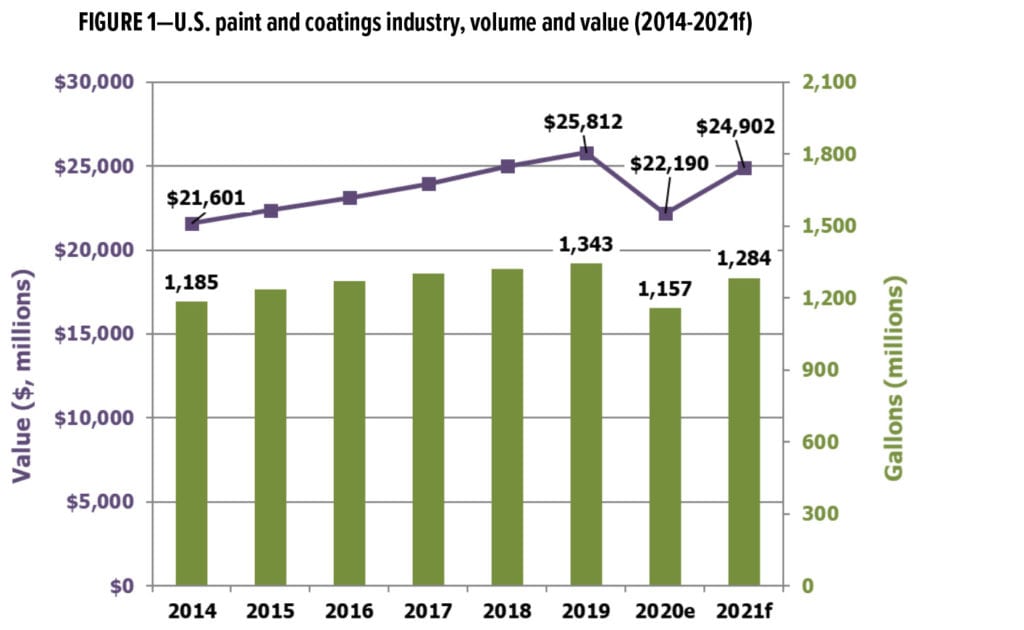

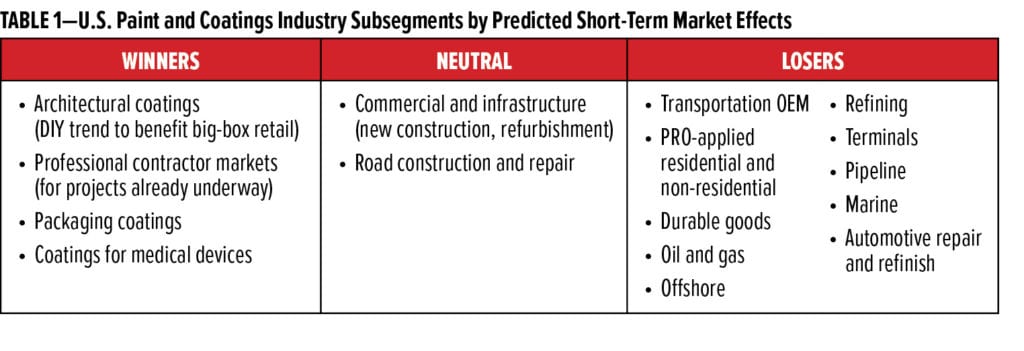

2020 is expected to be a mixed year for paint and coatings in the United States, with some “relative winners” but also with a number of definite “losers.” 2019 ended with production of 1.34 billion gallons valued at $25.8 billion, up 1.6% in volume and 3.3% in value from the previous year, but the outlook for 2020 suggests full-year production of 1.2 billion gallons valued at $22.2 billion, down 13.8% in volume and 14.0% in value (Figures 1–3, Table 1).

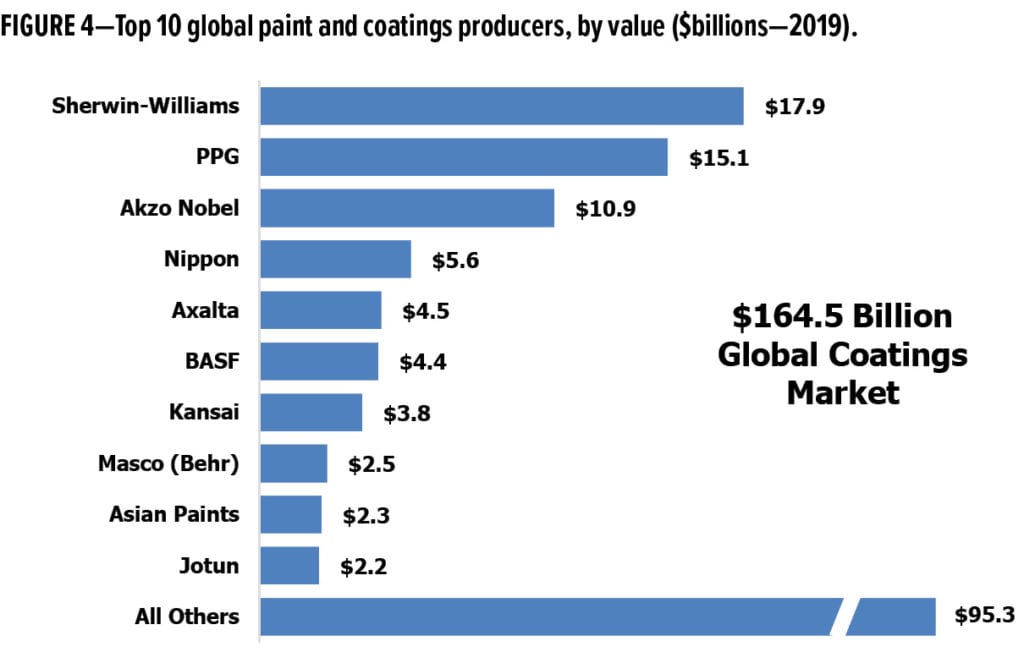

As a result of aggressive consolidation, the top 10 global coatings firms accounted for slightly greater than 42% of global sales in 2019, down from 50% five years prior. Taking this one step further, the top three global players accounted for 63.4% of sales by the top 10 coatings firms in 2019, virtually the same as in 2014, or five years prior. (Figure 4).

Architectural Coatings

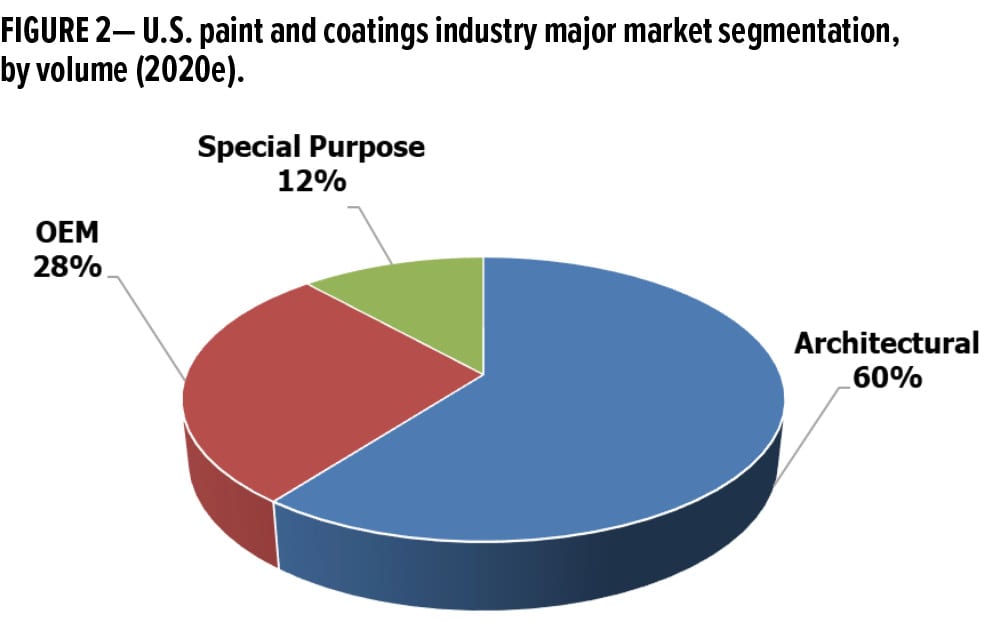

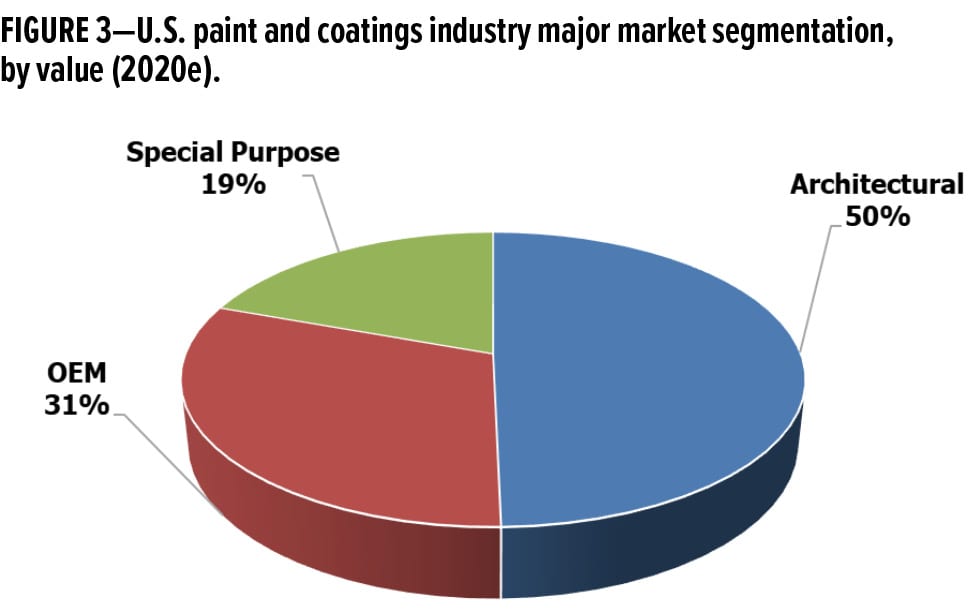

Architectural coatings sales are highly correlated with the health of the housing and construction market. The architectural paints segment currently accounts for 60% of the volume, and 50% of the value, within the U.S. coatings industry (Figures 2 and 3).

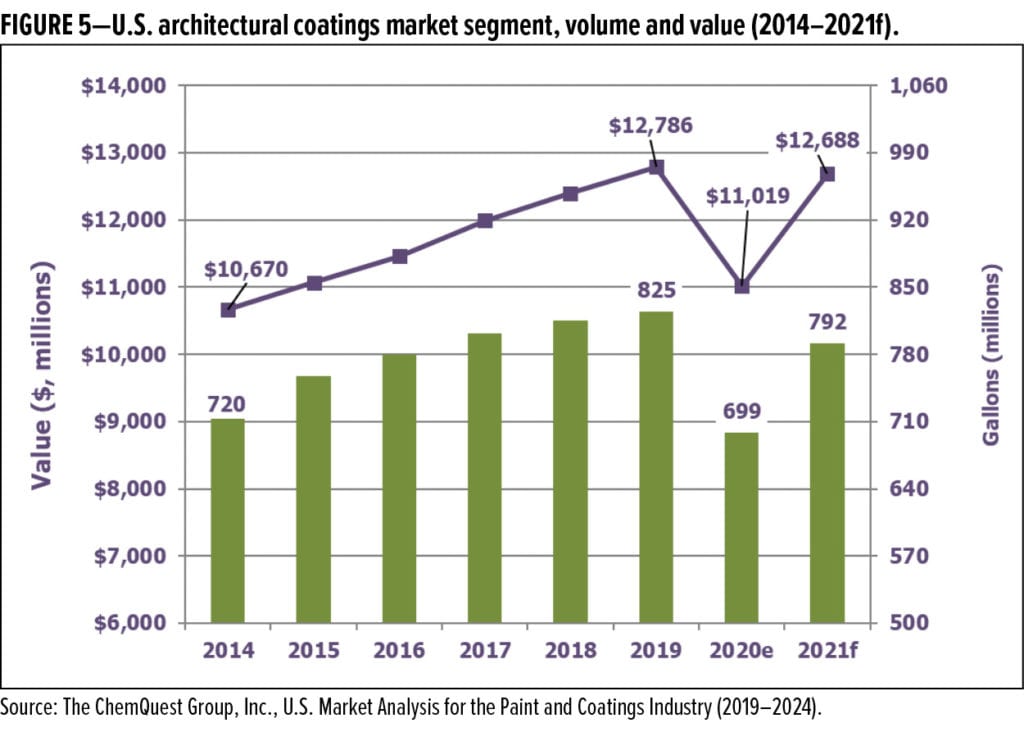

Architectural coatings grew 3.1% in value in 2019, compared to 2018, with volume growth of 1.2%. Sales were forecast to rise in 2020 pre-COVID, but we now estimate a decline of 15% in volume and a decline in value of 14% for 2020, resulting in volume of 699 million gallons valued at $11.0 billion (Figure 5).

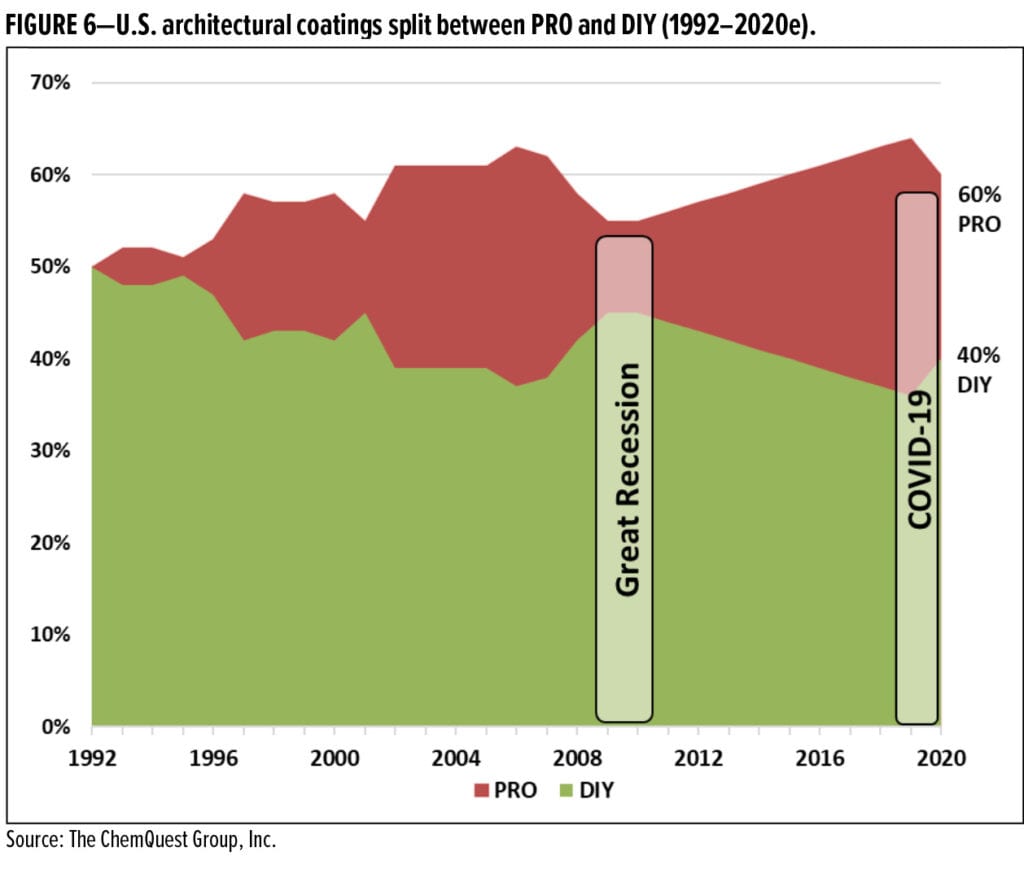

The percentage of PRO-applied paint has continued to grow, unabated, since 2012, reaching a relationship of 63–64% PRO to 36–37% DIY in 2019, the highest that this ratio has been since 2006 (Figure 6). Going forward into 2020, we had expected this relationship to stabilize, but the “COVID Effect” caused the PRO share to nosedive between mid-March and mid-May, as homebound consumers decided to purchase paint and apply it themselves, rather than hiring a PRO to do it for them. With the relaxation of shelter-in-place mandates, we would expect DIY activity to decrease, and PRO activity to increase—and this is precisely what began happening in mid-May. The rate of increase, however, will depend upon when the effects of COVID are mitigated, to what degree the homeowner’s behavior has become permanently altered and how long the post-COVID economic downturn lasts. As of mid-June, it seems reasonable to anticipate that the ratio of PRO:DIY for 2020 will end the year around 60%:40%, and PRO will continue to uptrend toward 62–63% during 2021 and 2022.

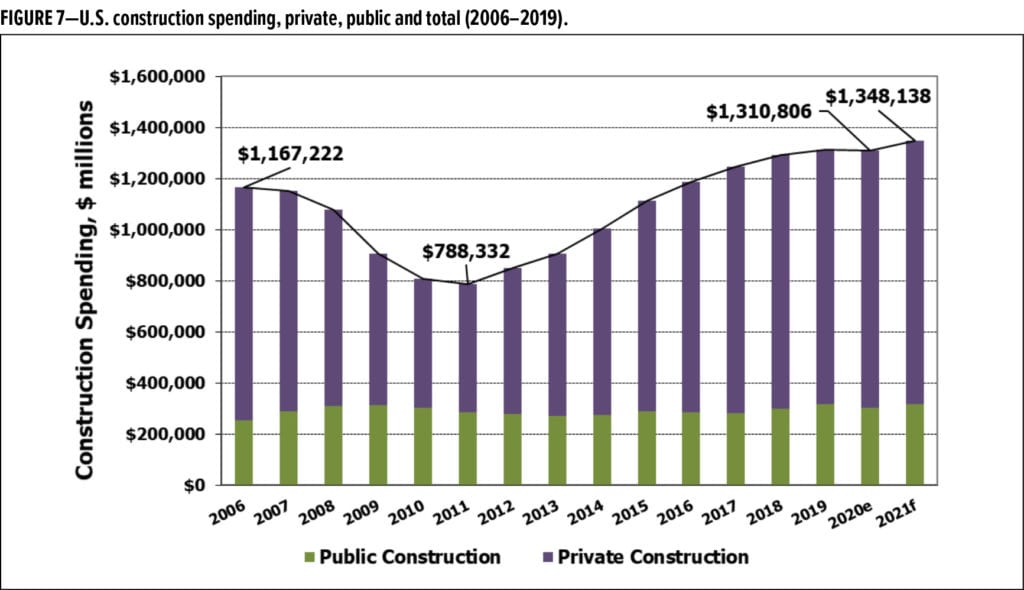

A major driver of the architectural coatings segment is construction, with which it has a very close correlation to coatings volume. Because construction in the United States in 2019 continued its prolonged recovery from the unprecedented low point experienced in 2011, this was good news for architectural paints and coatings. YoY, growth in construction spending for 2019 was 3.8%, but is anticipated to remain flat (or decline slightly) during 2020, due principally to the “COVID Effect.” (Figure 7).

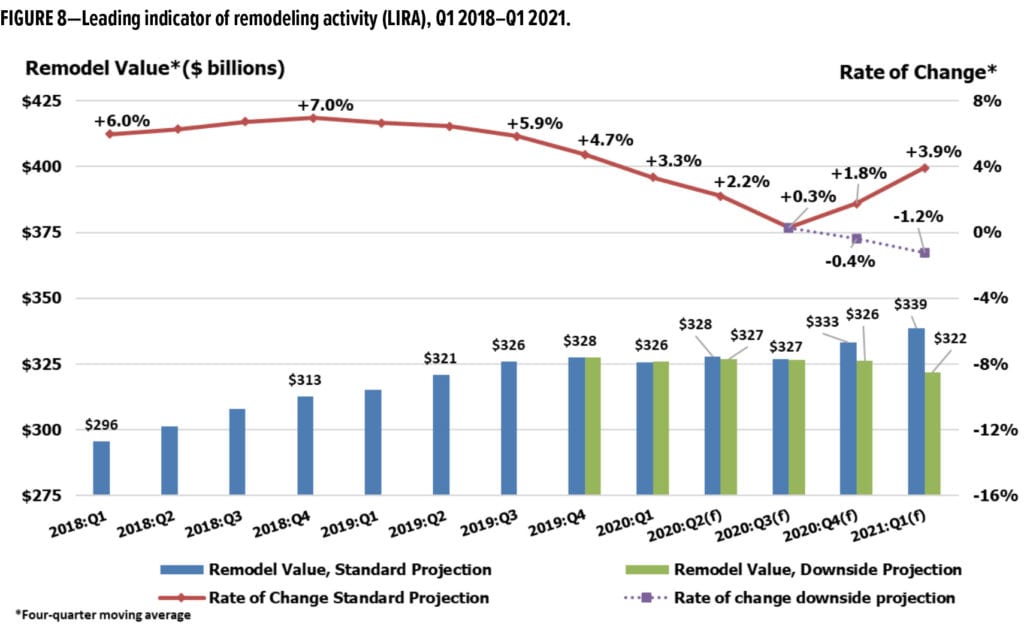

Another driver for the architectural coatings segment is remodeling, and the activity in this area is monitored by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University’s Leading Indicator of Remodeling Activity (LIRA). As shown in Figure 8, 2018 and most of 2019 were strong for remodeling, with a quarter-to-quarter growth of 6–7%. Remodeling began to slow toward the end of 2019 when compared to the very active growth in the earlier period—but was predicted to show increased growth beginning mid-2020. LIRA has now added a downside forecast that shows continued weakening at least through the first quarter of 2021.

Industrial OEM

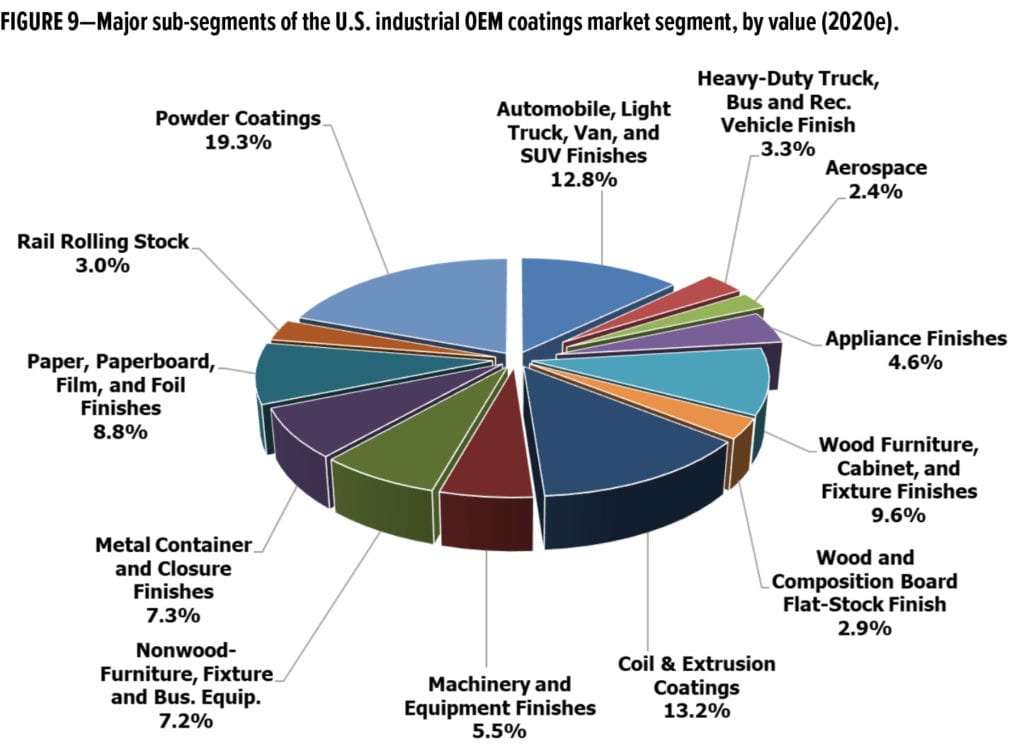

The industrial OEM segment is comprised of over a dozen sub-segments, of which appliances, HVAC, fireplaces, microwaves, automotive OEM (including rigid and flexible automotive exterior trim systems, brake systems, et al.), coil coatings, wood furniture and cabinets, and metal furniture and fixtures are a few representative coatings areas (Figure 9). The industrial OEM segment tends to be driven by a variety of factors, as a result of such a diversity of goods, although most are influenced by the macroeconomic environment, and especially by industrial production.

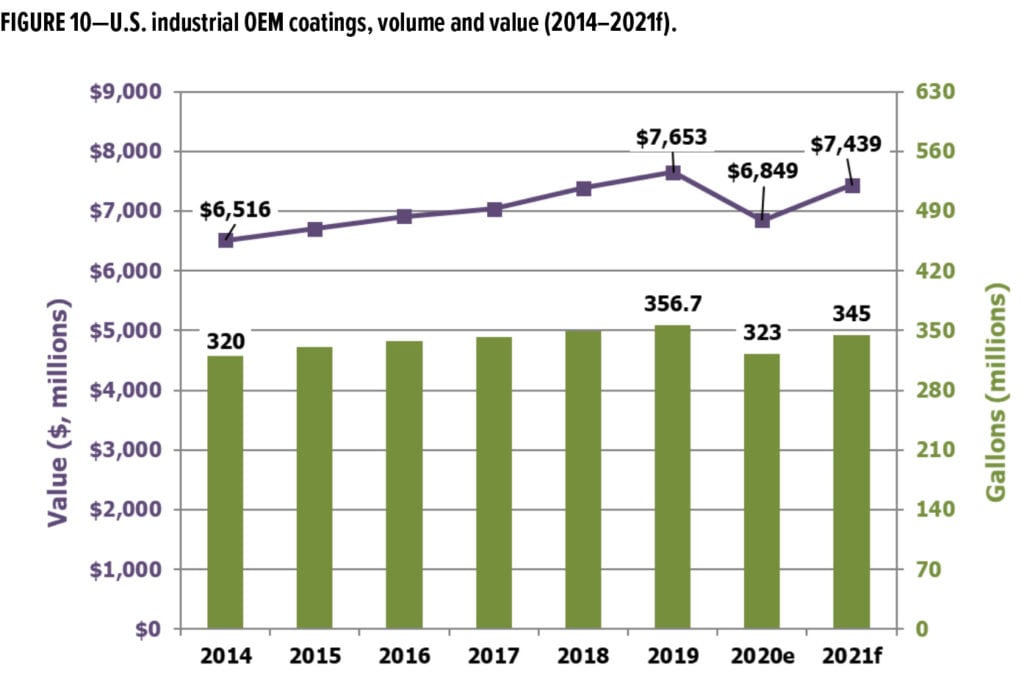

The U.S. industrial OEM segment grew in value 3.6% in 2019 (+2.1% volume; +1.5% price), generating $7.7 billion in sales (∼357 million gallons by volume), matching the peak in 2013. Due to COVID, however, the current 2020 forecast is for a decrease of 10.5% in value and 9.5% in volume, with pricing decreasing by 1.2% (Figure 10).

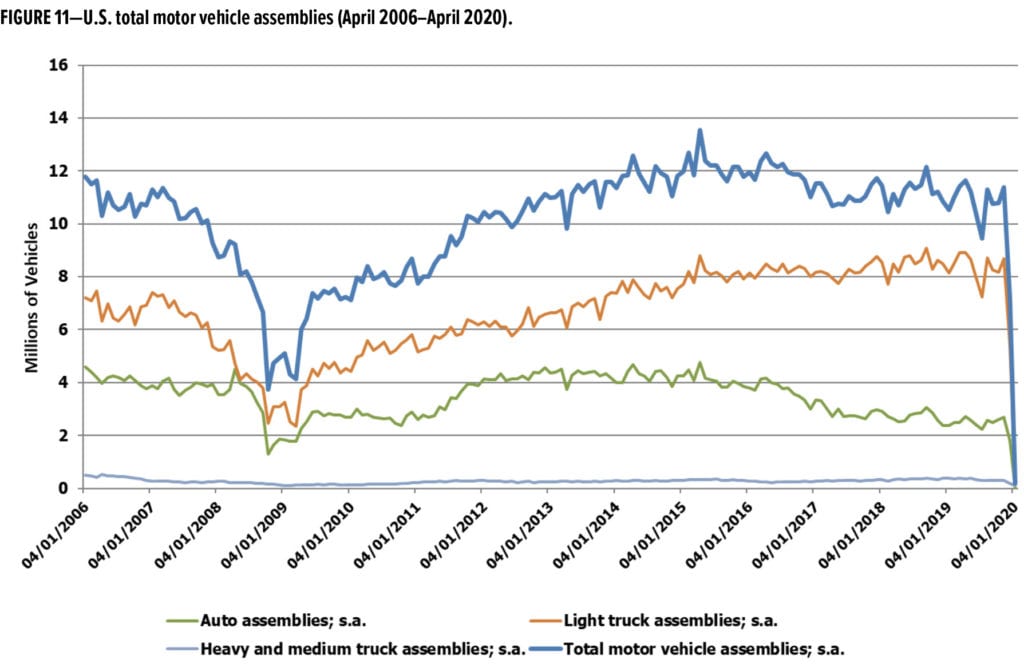

The year 2019 was not stellar for the automotive sub-segment (defined as automobiles, light trucks, vans, and SUVs; total of domestic production, transplants, and imports). The challenges continued into Q1 2020 with a further decline of 12.0%.16 Automotive OEM is forecast to decline by roughly 15% during 2020e17 (Figure 11). The “COVID Factor” is certainly responsible for a portion of the 2020 continued decline, but equally important are the effects of 2019 (i.e., pre-COVID) setbacks, such as slowing consumer spending due to increasing consumer debt, China trade conflicts, the imminent Brexit and general global economic slowdown.

Trends in the OEM market segment are driven by the need for products that create operational efficiencies (increased productivity/reduced labor/decreased cycle times); increased sustainability (reduce CO2 footprint and product end-of-life reuse/disposal); and continual innovation (infrared reflectance/noise vibration/insulation), et al.

Special Purpose Coatings

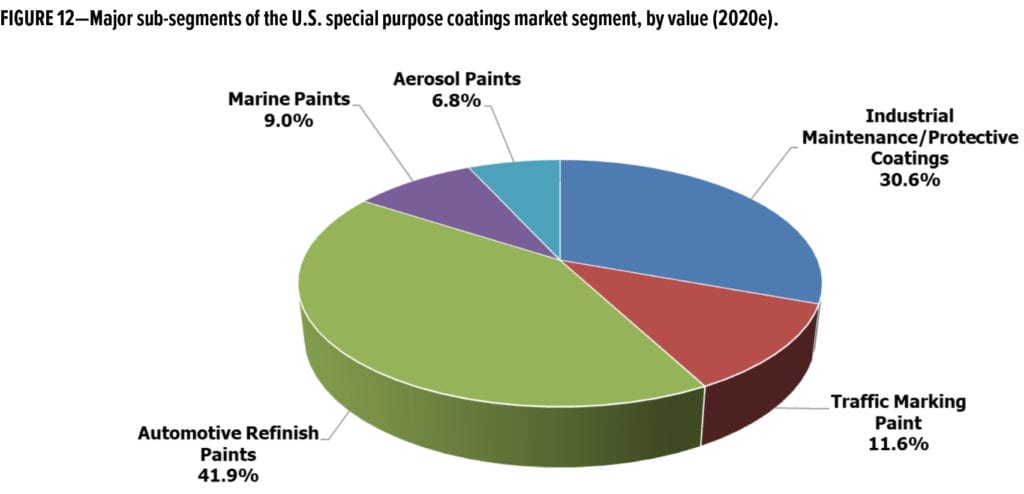

The major end-markets for special purpose coatings include automotive refinish, industrial maintenance/protective coatings, traffic-marking paints, marine coatings and aerosol paints (Figure 12). The special purpose coatings market segment serves far fewer end-market segments and sub-segments than industrial OEM coatings, but—as an overall segment—typically commands higher margins than OEM coatings.

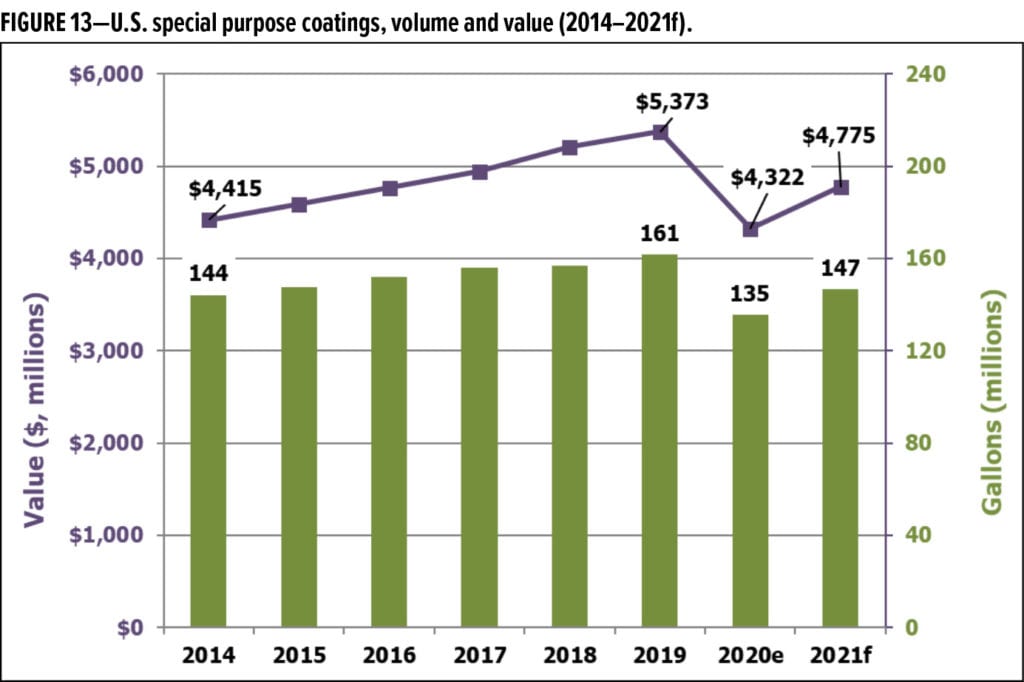

In 2019, special purpose coatings grew in value at a rate of 3.2% (+2.8% in volume; +0.4% in price) and contributed $5.4 billion (∼161 million gallons) of the $25.8 billion generated by the U.S. paint and coatings industry. This represents only 12% of the volume, but 21% of the value, of all coatings produced. In 2020, we are expecting a decrease in value of special purpose coatings, from $5.4 to $4.3 billion, with gallons decreasing to 135 million gallons (Figure 13). This represents a forecast sales dollar decline of ∼20% (∼16% in volume and ∼4% in price).

Special purpose coatings are dominated by automotive refinish coatings and industrial maintenance/protective coatings. As a result, this segment tends to track accident rates, automotive sales, size of the car parc (total number of registered vehicles in use at any given time) and total miles driven (refinish paints)—as well as industrial construction, infrastructure refurbishment, and crude oil prices.

Automotive refinish paints are directly tied to the accident rates, and indirectly to the total number of miles driven. Sales of automotive refinish coatings are, therefore, always teetering on the brink of growth vs decline, depending upon a number of conflicting factors that can dominate the situation at any given time. These factors include, but are certainly not limited to, improved education of the populace with regard to safer driving habits, as well as the advent of safer, “smarter” cars that help in accident avoidance and damage mitigation with an assortment of devices from energy-absorbing bumpers to back-up cameras, adjacent vehicle indicators and automatic controls that keep cars from accidentally crossing the center line. Also, insurance companies have been lowering the monetary threshold for declaring a vehicle to be “totaled.”

These factors, which negatively affect the sales of refinish coatings, are countered by other factors, such as the increase in disposable income, changing lifestyle and buying behavior, and demand for luxury vehicles, including crossovers and SUVs. These factors typically drive increases in the need for refinish coatings—e.g., luxury car owners tend to have scratches and minor dings repaired more readily than non-luxury vehicle owners. The latest driving distractions, such as talking, texting, and glancing at GPS screens while driving increase accident rates, and therefore benefit the automotive refinish coatings sub-segment. At any moment, however, external events, such as the COVID pandemic, hurricanes and other natural disasters, can tip the balance either way. Sheltering-in-place during COVID caused a steep drop in the number of drivers on the road, the number of trips being made and the number of miles being driven, resulting in a corresponding decrease in the need for automotive refinish coatings. With the passage of time, these various conflicting factors will settle down and mitigate against growth of the automotive refinish market, causing it to begin trending downward at an estimated 0.5–1.0% per year in volume during the period 2020–2024.

The industrial maintenance and protective coatings market segment represented 43.2 million gallons valued at slightly under $1.7 billion in 2019, an increase from 2018 of 2.1% by volume and 2.8% by value. Industrial maintenance and protective coatings consumption is directly tied to construction, maintenance of medium- and heavy-duty facilities such as petrochemical and wastewater treatment plants, infrastructure, and oil and gas production—and indirectly to global crude oil prices, which ranged from $67–$76/barrel in 2018 and $55–$65/barrel in 2019. We expect to see the price of brent crude hover around $40/barrel throughout 2020, and since certain subsegments of industrial maintenance and protective coatings, such as oil and gas, are negatively influenced by crude oil prices, a decrease in volume of protective coatings of 15% and a decrease in value of 17–18% can be expected.

On a global basis, marine coatings are directly related to shipbuilding activity which is cyclical in nature. Shipbuilding is principally concentrated in South Korea, Japan, and China (40%, 30% and 24%, respectively), with the remaining 6% parceled out to all other countries. Shipbuilding is not, therefore, a driver for the sale of marine coatings in the United States, where this subsegment primarily addresses the needs of pleasure craft, military ships, platforms, offshore supply vessels, etc. This market segment was valued at $473 million (9.8 million gallons) in 2019, up 2.8% in value and 2.1% in volume. As a result of both the price of crude oil and COVID, a decline in growth is expected in 2020 of -18% in value, and 19% in volume.

The U.S. Paint and Coatings Industry, On Balance

The year 2019 was a good one for the U.S. coatings industry, which grew 3.2% in value and 1.7% in volume. Pricing outpaced volume by 1.5%, which means that the coatings producers were able to keep ahead of raw material increases at an appropriate pace. Looking ahead to 2020, we estimate both volume and value to decline ~14%. Nonetheless, for the coatings industry, with a value of $22.2 billion on 1.16 billion gallons in 2020, the market remains large and relatively healthy, despite being short of predictions made as recently as January, immediately prior to the global pandemic—a pandemic that portends both a number of transient effects, as well as a lasting legacy in the form of a “New Normal.”

What will this “New Normal” be like? What types of behavior will be permanently changed? Will there be a decline in the construction of office buildings because many workers, who performed their jobs quite effectively from their homes, will no longer need—or want—offices? Will homeowners who discovered that doing their own painting was a lot easier than they thought, continue this activity into the future at a higher level than in the past few years, eschewing the use of PRO painters? Or, conversely, will they hire PRO painters in large numbers to fix their painting mistakes? Will the decline in building “brick-and-mortar” stores selling consumer goods continue, or perhaps even accelerate, as a result of a whole new group of people being sequestered in their homes, and discovering online shopping? What sorts of changes will we experience within the global economy, whatever that is? Will countries that previously outsourced production to lower-cost areas of the world begin repatriating a variety of businesses, as a result of the COVID crisis, revealing just how vulnerable their supply chains were?

The answers depend entirely upon who is asking the questions, and who is answering them. Paint and coatings producers concerned only about this quarter’s earnings may be inclined to simply “roll with the punches” and do their best to play catch-up with the changing times. This approach is most certainly not good enough, however, for those companies that are less concerned about this year than they are about 5–10 years from now. The management team of this latter group understands that the information in this article only has value when it is used to predict—and prepare for—trends in the future, using past experience and solid knowledge of the market dynamics and general mindset of the present. Technology-based industries are constantly in need of newer, safer, more durable, more sustainable and more user-friendly products, manufactured from secure supply chains—and the global “COVID disaster” has highlighted disruption in supply chains due to weak links that must be addressed before the next global disruption occurs.

. . . The market remains large and relatively healthy, despite being short of predictions made as recently as January, immediately prior to the global pandemic . . .

It is certainly important for strategic, forward-looking companies to make money this year so that they will still be in business next year—that just makes good fiscal sense, and it definitely requires some tactical maneuvering along the way. They recognize, however, that year-on-year of nothing but tactical decisions will eventually lead nowhere, and that unless they take a strategic approach to their business, there is a tombstone somewhere in the future with their name on it. Making money to stay in business this year is necessary, but creating new products is essential to remaining in business in the future. One need only think back a relatively short number of years to recall past paint and coatings producers that were either driven out of business or were acquired as the result of a lack of innovation and organic/inorganic growth strategies—or simply chose to close their doors because they were tired of treading water. Unfortunately, these are the options for paint producers that have chosen to sacrifice their future on the altar of the tactical. In the “New Normal,” strategic management is going to be more important than ever before to maximize a company’s chances for survival.

We do not know when the COVID crisis will end, or if it will appear to end, but then rear its ugly head again in 2020 or even beyond. The long, slow, unexciting recovery from the Great Recession period officially ended this past February, and many enterprises that made it through that period are now facing a new COVID-induced economic downturn that will claim some victims, especially ones that are living on a quarter-to-quarter basis. For those companies with a concise, carefully considered and clearly articulated strategy for the future, however, their reward will be that they will weather the post-COVID period and be the first to introduce exciting new products and processes for an eager and receptive marketplace. They will also be manufacturing these products with revised processes and procedures, not only regarding supply chain considerations, but very probably with a somewhat different approach to the deployment of human resources and physical assets, as well.

Whether these companies create their strategies and new products on their own, or work with outside partners—strategic business and/or technology consultants, independent laboratories, universities or all four—should be the subject of serious discussion in a changing world where in-house assets are increasingly challenged and easily overwhelmed. Ultimately, having a strategy—

and implementing that strategy—is of paramount importance, because this is what will separate the winners from the losers, following the most devastating global disruption of the modern era.

References

- The 90% Economy. The Economist, May 2, 2020, p 7.

- Lowenstein, R. History Repeating. The Wall Street Journal, January 14, 2015.

- Trading Economics. https://tradingeconomics.com/china/gdp-growth (accessed July 15, 2020), China GDP Growth Rate.

- China Reports Rising Industrial Production but Falling Consumer Spending in April. MarketWatch, May

15, 2020. marketwatch.com/story/china-

reports-rising-industrial-production-but-falling-

consumer-spending-in-april-2020-05-15 (accessed July 15, 2020). - Maake, K. Marriott Encouraged by Hotel Business’ Recovery in China as U.S. Inches Toward Reopening. Triangle Business Journal, May 12, 2020.

https://www.bizjournals.com/triangle/news/2020/05/12/

marriott-encouraged-by-hotel-business-recovery-in.html (accessed July 15, 2020). - He, L.; Gan, N. 80 million Chinese May Already Be Out of Work. 9 Million More Will Soon Be Competing for Jobs, Too. CNN Business, May 6, 2020. cnn.com/2020/05/08/economy/china-unemployment-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed July 15, 2020).

- Feng, J. More Than 240,000 Chinese Companies Declare Bankruptcy in the First Two Months of 2020. SupChina, April 9, 2020. https://supchina.com/2020/04/09/more-than-240000-chinese-companies-declare-bankruptcy-in-the-first-two-months-of-2020/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

- Beaumont, H.; Fingerhut, H. AP Poll: Americans Harbor Strong Fear of Second Wave of Coronavirus Infections, Back Precautions Amid Openings. Chicago Tribune, May 20, 2020. chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-nw-poll-coronavirus-attitudes-20200520-5mzt7qichje5zojh27mv2z6ki4-story.html (accessed July 15, 2020).

- Andersen, A. L.; Hansen, E. T.; Johannesen, N.; Sheridan, A. Pandemic, Shutdown and Consumer Spending: Lessons from Scandinavian Policy

Responses to COVID-19. University of Copenhagen and Center for Economic Behavior and Inequality. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.04630.pdf (accessed July 15, 2020). - Pietsch, B. Sweden’s Economy Likely Won’t Benefit From Its Decision to Avoid a Lockdown, According

to Analysts. Business Insider, May 17, 2020.

businessinsider.com/sweden-economy-

likely-wont-benefit-from-decision-avoid-lockdown-

report-2020-5 (accessed July 15, 2020). - Bogaisky, J. Boeing To Slash Output of 787 and 777, Cut 16,000 Jobs as Coronavirus Delivers ‘Body Blow’. Forbes, April 29, 2020.forbes.com/sites/

jeremybogaisky/2020/04/29/boeing-to-slash-output-of-787-and-777-reduce-workforce-by-10/#6781410e7aae (accessed July 20, 2020). - Continued Government Relief Measures Needed to get Airlines through the Winter, 2020. International Air Transport Association Press Releases. iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-06-16-01/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

- Park, K. Airlines Brace for $113 Billion in Lost

Revenue from Virus. Bloomberg, March 5, 2020. bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-05/airlines-see-up-to-113-billion-in-lost-2020-revenue-on-virus (accessed July 15, 2020). - Continued Government Relief Measures Needed to get Airlines through the Winter, 2020. International Air Transport Association Press Releases. iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-06-16-01/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

- Chokshi, N. The Airline Business Is Terrible. It Will Probably Get Even Worse. The New York Times, May 10, 2020. nytimes.com/2020/05/10/business/airlines-coronavirus-bleak-future.html (accessed July 15, 2020).

- US 2020. Mazda (+10.9%) & Volvo (+4.5%) Impressed in Market Down Again 25%, 2020. Focus2Move.focus2move.com/usa-vehicles-sales/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

- Higgins-Dunn, N. US Auto Sales Expected to Fall at Least 15% This Year Due to the Coronavirus. CNBC, March 25, 2020. cnbc.com/2020/03/25/coronavirus-us-auto-sales-expected-to-fall-at-least-15percent-this-year.html (accessed July 15, 2020).

CoatingsTech | Vol. 17, No. 8 | August 2020