The efficacy of the active biocide ingredients used in antifouling bottom paint to contain and impede the growth of biofouling on boat hulls is of global economic concern, given that costs associated with mitigating the damage caused by invasive species are escalating, especially in coastal waters where fouling nutrients are concentrated. The efficacy of an antifouling coating depends on site-specific fouling pressure where the vessel operates, which biocide(s) are used in the formulation, and the biocidal release rate from the painted surface to the ambient water. Coatings formulated with cuprous oxide have been around for at least 100 years, and are applied to an estimated 90% of the world’s vessels whose hulls are protected with biofouling control coatings. Historically, copper has been repeatedly challenged and subsequently reviewed for its risk and effectiveness, and is arguably the most researched substance for toxicity in the marine environment. Likewise, copper-based antifouling paint has been repeatedly tested for efficacy in hundreds of coatings formulations by multiple manufacturers. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to characterize copper-based antifouling coatings as proven technology.

Yet, the sale and use of copper-based antifouling paints formulated to protect recreational boat hulls in the United States is under closer scrutiny than ever before. Recent proposals submitted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) have expanded the focus of restricting the use of copper, while such restrictions have heretofore been confined to the states of Washington and California, and a handful of municipalities in the United States. This trend, should it continue, threatens the use of proven antifouling technology on recreational boats—posing larger economic questions not only for the boating public whose vessels require effective antifouling bottom paint to curtail higher fuel consumption and hull maintenance costs linked to friction and drag as the result of biofouling accumulation—but also for port districts, municipalities, and marinas that must bear the cost of containing invasive species.

Manufacturers continue in their efforts to provide effective (and compliant) copper and copper-free antifouling bottom paint products to meet customer requirements in an ever-changing regulatory environment.

As a sequel to the September 2016 CoatingsTech article entitled, “Marine Coatings: Making Sense of U.S., State, and Local Mandates of Copper-Based Antifouling Regulations,” this article reviews recent legislative actions, explaining the ramifications of new and pending legislation from various perspectives. The authors conclude with what the future holds for antifouling bottom paint.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Copper-based antifouling paint came under scrutiny by regulatory authorities in San Diego, CA, when the Shelter Island Yacht Basin was found to have levels of copper exceeding the 3.1 mg/L limit permitted under The Clean Water Act (CWA). Numerous actions have been instituted or investigated, including requiring hull cleaning divers to use best management practices, encouraging and testing the use of alternative coatings, and establishing alternative but environmentally protective water quality standards, as part of the solution toward bringing the harbor into regulatory compliance for copper by 2022. Nevertheless, the use of copper-based antifouling bottom paint for recreational vessels has been under further scrutiny by Washington, California, and the U.S. EPA.

The State of Washington—Ssb 5436 (April 2011)

Biocidal paints must be registered with the U.S. EPA and the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA). WSDA staff review labels and documents from manufacturers for compliance with state law. Selected data are stored in the Pesticide Information Center Online (PICOL) Database (Washington State University, 2017). In 2011, the Washington State Legislature passed the Recreational Water Vessels—Antifouling Paints Law, Revised Code of Washington (RCW) Chapter 70.300, to phase out the use of copper-based antifouling paints on recreational boats. A recreational vessel is defined in the law as being no more than 65 feet in length, and used primarily for pleasure boating. As of January 1, 2018, Washington law bans the sale of new boats with copper-based antifouling paint. However, the state of Washington has proposed legislation—to be considered in the legislative session that began January 8, 2018—which would delay this ban until January 1, 2021. While the bill is being considered by the Legislature, state resources will not be dedicated to enforcement. If the Legislature chooses to leave the ban in place, state officials have indicated they will “reprioritize and start enforcing the ban as needed and as resources permit.”

>Why has the state of Washington delayed the ban?

State officials concluded there is not a proven, superior biocide alternative to copper. While the state of Washington’s Department of Ecology seeks to reduce copper pollution found in its marinas that state officials have attributed to copper leaching from copper-based antifouling bottom paints, they fear any alternate biocide used in bottom paint as an active ingredient may cause more environmental damage than copper, threatening water quality and damaging Washington’s environment. Therefore, state officials have recommended delaying the ban of copper-based bottom paint, so they may have ample time to study the relative impacts of copper versus non-copper biocides, using models based on Puget Sound marina designs and water quality conditions.

The second phase of the bill, slated to go into effect January 1, 2020, would ban the sale of antifouling paints for recreational boats if the paints contain more than 0.5% copper.

Section 2a of the bill sought industry comments through 2017, following a survey of manufacturers of antifouling paints to determine the types of antifouling paints that are available in the state of Washington. The Department of Ecology stated it would also study how antifouling paints affect marine organisms and water quality. All study findings were promised to be reported to the Legislature, consistent with RCW 43.01.036, by December 31, 2017.

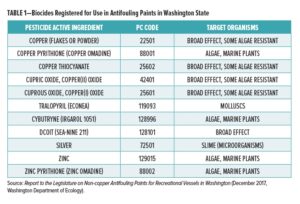

The survey of manufacturers identified the following formulation types of antifouling paints registered for use in Washington State. Note that the following figures are not adjusted for double counting of toll-manufactured store brands:

- 123 antifouling paints containing some form of copper

— Of the 123, 90 paints were based on copper alone, mostly in the form of cuprous oxide.

— None of the copper-containing paints meet the 0.5% copper maximum limit described in RCW 70.300.020. Therefore, they would all be subject to the law’s 2020 ban on use and sale.

- A total of 11 biocides are registered for use (as shown in Table 1).

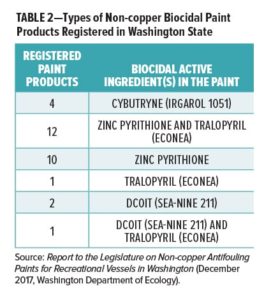

- 30 non-copper biocidal antifouling paints (as shown in Table 2).

- Several types of non-biocidal paints.

The non-copper biocides identified in the survey include six different types, based on the use of a single non-copper biocide or a combination of two non-copper biocides. According to unspecified studies conducted by other countries, any of these non-copper biocides “may pose” a significant risk to marine life and water, according to the Washington Department of Ecology. However, the conditions found in Washington’s waters reportedly differ from conditions studied outside the United States. The impact of non-biocidal paints on marine life is unknown, as it has never been studied. Moreover, the Department of Ecology would require aquatic toxicity testing

The non-copper biocides identified in the survey include six different types, based on the use of a single non-copper biocide or a combination of two non-copper biocides. According to unspecified studies conducted by other countries, any of these non-copper biocides “may pose” a significant risk to marine life and water, according to the Washington Department of Ecology. However, the conditions found in Washington’s waters reportedly differ from conditions studied outside the United States. The impact of non-biocidal paints on marine life is unknown, as it has never been studied. Moreover, the Department of Ecology would require aquatic toxicity testing

to determine the effects (if any) of non-biocidal antifouling paints on marine life.

Washington State’s criteria for the “ideal biocide” specifies that the biocide’s lifecycle in the environment should be short in duration, with low bioaccumulation, and low toxicity to non-fouling species, albeit what they consider to be “short” and “low” is not included.

For more details on the state of Washington Department of Ecology’s risk assessment models and benchmarks, results for non-copper biocidal paints, and additional study findings, are published online in their December 2017 report entitled, Report to the Legislature on Non-copper Antifouling Paints for Recreational Vessels in Washington, go to https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/SummaryPages/1704039.html.

A summary of Washington State’s recommendations includes:

- Collect additional scientific data and information about biocides. Biocide assessments conducted by governments in other countries suggest that the use of paints with certain non-copper biocides may have an adverse effect on water quality and marine life in the Puget Sound. The Department of Ecology recommends working with the U.S. EPA, other regulatory authorities, paint manufacturers, and other interested parties to collect scientific data and information on the use and safety of these biocides.

- Investigate and model biocide risk based on Washington State data. High quality scientific models are available that can quantify the risk of biocides in marina environments. The Department of Ecology recommends using these models with data for Washington State water conditions and marina characteristics to validate whether the high risk estimated in other countries is relevant to marinas here. These models can also be used to address sediment impacts and freshwater marina considerations.

- Evaluate efforts by U.S. EPA and other states to adopt leach rate limits. To mitigate the effects of copper, the state of California has recently implemented a leach rate limit for copper-based antifouling paints used on recreational vessels. Interim reports from the registration review of copper at the U.S. EPA suggest that similar leach rate limits may be proposed nationally for saltwater recreational antifouling applications. The Department of Ecology intends to evaluate these regulatory actions for applicability in Washington State.

- Incorporate findings from recent antifouling paint assessments. Northwest Green Chemistry (NGC), a nonprofit organization, worked with the Department of Ecology, industry, and other organizations to conduct research and publish an alternatives assessment of copper-based antifouling paints. Washington State will integrate the results from their analysis of copper-free alternative paints into ongoing work to determine whether there are safer options.

- Establish a public-private partnership to assess the performance of antifouling paints. NGC assessments of the performance of antifouling paints rely on limited data, mostly from warm-water locations. The Department of Ecology recommends forming a public-private partnership to conduct performance field tests of antifouling paints in Washington waters to assess whether performance data from other jurisdictions is relevant to Washington waters and fouling species.

- Collaborate with the private sector to promote safer alternatives and best practices. The Clean Boating Foundation’s Clean Boatyard Program works to disseminate best management practices for boatyards to reduce the impact of toxic substances on nearby waters (Clean Boating Foundation, 2017). The Department of Ecology recommends working with this program to promote source control and reduction strategies and to share current and future findings on the safest available antifouling paint alternatives.

- Promote the use of alternatives assessments. The Department of Ecology recommends promoting ongoing alternatives assessments of new paint technologies as they are developed, but also for innovative technologies such as boat washing stations. Efforts in this area can help avoid the use of regrettable substitutes and, where possible, identify non-chemical solutions to our environmental challenges.

California’s AB 425—2013

Senate Bill 623, introduced by Senator Christine Kehoe in February 2011, would have, as written, banned the use of copper in antifouling coatings on recreational vessels in the state of California. However, SB 623 was not passed into law. The additional cost to the recreational boat owner of alternatives, the unproven efficacy of alternatives, and the concern of additional transport and introduction of invasive species due to biofouling on recreational vessels, were three reasons a different approach was instituted.

Assembly Bill 425 was passed and included a mandate for the hull cleaning study, which was later used to determine the leach rate. As noted in our September 2016 CoatingsTech article, the state of California’s antifouling registration renewal program notified antifouling coatings manufacturers in March 2011 that they were required to fund a comprehensive study to evaluate the contribution underwater hull cleaning made to copper in water coves. Study findings indicated that underwater hull cleaning contributed up to 50% of copper detected in the water. Earley, Swope, Barbeau, Rundy, McDonald, and Rivera-Duarte’s acclaimed paper, “Life Cycle Contributions of Copper from Vessel Painting and Maintenance Activities,” puts that study finding into proper perspective by concisely characterizing the chemistry of copper levels that exceed water quality criteria. (Note: Earley’s full paper is available on the NIH.gov website. The study was conducted under requirements established by the DPR.)

Moreover, AB 425 stated “no later than February 1, 2014, the Department of Pesticide Regulation shall determine a leach rate for copper-based antifouling paints used on recreational vessels and make recommendations for appropriate mitigation measures.” The result of this calculation is a leach rate effective January 1, 2018 equal to or less than 9.5 μg/cm2/day, resulting in loss of registrations of antifouling products above that leach rate on July 1, 2018. In addition, a key strategy that the California Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR) is counting on is improved in-water hull cleaning best management practices to mitigate against spikes in dissolved copper concentration levels.

California’s Marina Del Rey Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL)

The Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board has approved the development of a site-specific objective (SSO) for dissolved copper in the Marina del Rey Harbor. Simply put, rather than using one-size-fits-all dissolved copper levels called out in the Clean Water Act to regulate Marina del Rey, a designated scientific group will scientifically quantify the actual toxicity limit of copper in that water body. Site-specific objectives for dissolved copper are, by far, the most accurate implementation method of protective standards and actions while preventing the waste of resources in attempting to meet standards that are not appropriate for a given water body. These benefits have been demonstrated in other water bodies such as San Francisco Bay.1

Once the SSO is determined, it will be presented to the LA Regional Water Quality Control Board for approval as the new objective for that water body (i.e., it will become a new scientifically established environmentally protective concentration limit for copper specific to the site of Marina del Rey Harbor). Moving forward, it would serve as the newly established goal or standard.

In addition, by June 2018, the State Implementation Plan (SIP) has approved that 25 recreational vessels be painted with alternatives to copper-based antifouling coatings (and 100 recreational vessels painted with copper alternatives by 2020). Their intent is to make the boating public aware of non-copper-based coatings that may meet the needs of the recreational boater in terms of efficacy and economic viability (e.g., life-

cycle coatings costs) benchmarked against copper-based antifouling coatings. The ultimate goal of the actions being taken in Marina Del Rey is to bring that water body into copper concentration compliance by 2024.

Amendment to the California State Lands Commission’s Biofouling Management Regulations for Vessels Arriving at California Ports

As of October 1, 2017, an amendment to the California State Lands Commission biofouling management regulation (title 2, California Code of Regulations section 2298.1 et seq.) requires all vessels capable of carrying ballast water to submit the Marine Invasive Species Program Annual Vessel Reporting Form to the California State Lands Commission’s Marine Environmental Protection Division 24 hours in advance of the first arrival at a California port for each calendar year.

If a vessel arrived at a California port in 2017 prior to October 1, this form is not required for 2017, but rather, the vessel must submit the now-repealed Hull Husbandry Report Form and the Ballast Water Treatment Technology Annual Reporting Form (if applicable). Beginning on January 1, 2018, the requirement for completing the commission’s Hull Husbandry Report Form, the Ballast Water Treatment Technology Annual Reporting Form (and the Ballast Water Treatment Supplemental Report Form) has been repealed to streamline reporting requirements for ship operators.

According to the commission’s Initial Statement of Reasons, this amendment is intended to “encourage the use of best management practices, including the appropriate use of antifouling or foul-release coatings (i.e., using coatings aged within their effective coating lifespan).”

Biofouling management regulations require ocean-going vessels entering the ports of California to have minimum biofouling on the underwater portion of their hulls and niche areas. Ships having a hull husbandry report that verifies the coating on the hull is still within the specified lifetime will be presumed to be in compliance. A ship whose coating is beyond its life span, or is not using an antifouling coating at all, will be inspected and must not exceed 5% biofouling on the hull and not more than 15% in niche areas, albeit several niche areas are exempted for safety reasons. The American Coatings Association (ACA) expressed support for the streamlined reporting measure that lessens the burden on ship operators, and encourages the use of efficacious antifouling coatings.

ACA, which is both a member and Secretariat for the International Paint and Printing Ink Council (IPPIC), also offered the commission use of an IPPIC-developed template for the completion of a biofouling management plan. IPPIC worked with IMarEST (The Institute of Marine Engineering, Science and Technology) to develop the template, which can be used as a tool for the implementation of the International Maritime Organization’s 2011 Guidelines for the Control and Management of Ships’ Biofouling to Minimize the Transfer of Invasive Aquatic Species. This template was recently submitted by IPPIC and IMarEST (a major maritime NGO) to the International Maritime Organization at the 70th Session of the Marine Environment Protection Committee that met in London in October 2016.

ACA believes this template meets the California commission’s objectives, and urged the commission to consider accepting the IPPIC template in lieu of the proposed SLC form. Given that vessels can operate in a wide variety of regulatory environments, allowing operators to use a consensus document such as the IPPIC document could be a sensible alternative to the proposed form, according to ACA.

Details on this amendment can be found online at https://www.slc.ca.gov/Programs/MISP.html.

U.S. EPA ACCEPTING COMMENTS ON DRAFT COPPER RISK ASSESSMENT

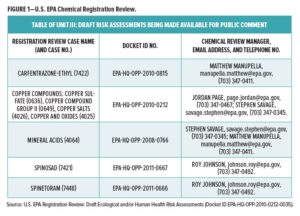

The U.S. EPA periodically reviews pesticide registrations under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act “to ensure that each pesticide continues to satisfy the statutory standard for registration, that is, the pesticide can perform its intended function, without unreasonable adverse effects on human health or the environment (based on current scientific and other knowledge).” To that end, the U.S. EPA had accepted public comments on its Registration Review: Draft Ecological and/or Human Health Risk Assessments for copper. While the agency’s risk assessment does not address organic copper registrations, it does include copper sulfate, copper group II, copper salts, complexes, hydroxides, and oxides. U.S. EPA had previously completed comprehensive draft human health and/or ecological risk assessments for all chemicals listed in the Table of Unit III (Figure 1).

The agency’s subsequent risk assessment (with a recreational vessel focus) is considering copper leach-rate limits for antifouling coatings such as those imposed in the state of California.

During the public comment period ending December 22, 2017, in the agency’s Interim Report, the copper antifouling coating registrants (that includes the copper active ingredients’ registrants as well as the paint formulators) submitted comments on the data the U.S. EPA is considering collecting. Registrants suggested the agency collect a smaller data set. Registrants also volunteered to work with the agency to collect coatings’ use and existing toxicity data.

Currently, the copper antifouling coating registrants are in discussion with the U.S. EPA about the most effective action plan to mitigate U.S. EPA concerns related to copper concentrations found in recreational marina waters. In a conference call scheduled for early February 2018, registrants had an opportunity to discuss the specifics of the action plan with the U.S. EPA, including how best to proceed, given that U.S. EPA has now had time to review registrants’ submitted comments.

U.S. EPA INVESTIGATING AN IMPROVED METHOD TO ESTABLISH SITE-SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

In the September 2016 CoatingsTech article, we reported that the Recreational Boaters of California (RBOC) had been urging the U.S. EPA’s Office of Water to approve the Marine Biotic Ligand Model for Copper in salt water to ensure that more accurate marine and estuarine water quality criteria was developed. The BLM will allow for for more scientifically objective benchmarks as the basis for SSO for use in TMDL regulations versus the current one-size-fits-all methods. At the time of publication of this article, the U.S. EPA has not yet completed its work on the BLM to scientifically determine SSOs.

REGULATORY DISPARITY

Several studies conducted in Shelter Island Yacht Basin (SIYB), determined that the majority of the basin had dissolved copper concentrations that exceeded the U.S. EPA Clean Water Act and California Toxics Rule (CTR) criteria, but also determined that there was only one spot in the marina (at the farthest distance inside the basin) in which statistically significant effects on mussel larvae were reported.2 Neal Blossom, ACA Marine Coatings Committee Chair, contends that when it comes to achieving a goal of non-toxicity for non-target species, establishing an SSO will provide reasonable assurance of environmental protection. Put another way, exceeding criteria that is set forth in the Clean Water Act and observing actual toxicity in the environment are disparate.

In fact, agencies attempting to work in tandem with one another can find themselves working at cross purposes due to their incongruent goals.

Consider the U.S. EPA Organization Chart: The Office of Water (OW) is responsible for implementing the Clean Water Act, and similar statutes designed to maintain aquatic ecosystems to protect human health; support economic and recreational activities; and provide healthy habitat for fish, plants, and wildlife. Copper-based antifouling coatings registrants must obtain approval from the U.S. EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP), which oversees periodic pesticide registrations and reviews, and regulates pesticide use to prevent significant adverse effects on non-target organisms. The state of California’s organizational chart and regulatory objectives are nearly identical to the U.S. EPA’s two offices. In theory, both offices can concurrently meet their regulatory goal. However, a third agency responsible for a given water body, such as the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board that is responsible for the SIYB, may be required by the Clean Water Act or the California Toxics Rule to meet a water quality standard when no significant adverse effects to non-target organisms have been measured. Therefore, an action of meeting a water quality goal must be taken by the agency responsible for a water body, even in the absence of measurable toxicity (or measured at minimal levels in a small geographic area of the water body in question).

CONCLUSION

Copper-containing antifouling coatings are a proven efficacious technology to reduce biofouling on recreational and commercial vessels, as shown by their overwhelming market share. This efficacy is critical to provide the vessel owner with a clean hull that travels well through the water with limited drag and lower fuel usage. It is also critical to minimize the extremely detrimental and long-term environmental damage caused by the introduction of invasive species. However, recreational marinas by their very design for berthing a multitude of vessels in a small area with low flushing can create conditions whereby copper concentration exceeds existing water quality standards. The use of new studies to determine more appropriate and protective standards for each water body can ensure that the environment is protected while preventing the waste of resources and effort to achieve nonproductive outcomes. As regulators have determined, there is no risk-free, simple answer to the biofouling challenge. Federal and state regulators are working with industry and recreational boaters to allow efficacious coatings that protect the environment from invasive species and excessive fuel use while minimizing negative consequences in recreational marinas from copper and other antifouling coating biocide and chemical inputs to the environment. Copper continues to prove itself to be an effective active ingredient in antifouling coatings with limited negative effects. Where those effects are found to be of concern, copper leach-rate limits, best hull management practices, and alternatives coatings, have been proposed to environmentally protect recreational marinas.

Endnotes

- The necessity of SSOs, including substantial reductions achieved in copper wastewater loading to the Bay over the past two decades, are presented by Richard Looker in the California Regional Water Quality Control Board’s Copper Site-Specific Objectives in San Francisco Bay—A Proposed Basin Plan Amendment and Draft Staff Report (dated June 6, 2007, 107 pp).

- 2. The Copper Bioavailability and Toxicity to Mytilus galloprovincialis in Shelter Island Yacht Basin, San Diego, CA study, prepared by Casey Bosse, Ignacio Rivera-Duarte, Gunther Rosen, Marienne Colvin, Brandon Swope, and Patrick Earley (representing the University of San Diego, SPAWAR System Center Pacific, and the San Diego State University Research Foundation, respectively) findings: “Although copper in SIYB are elevated in comparison to the main body of San Diego Bay, the ambient water is generally not toxic to mussel embryos (1 out of 62 samples somewhat toxic), and that dissolved copper as high as 8.8 μg L-1 were not toxic to mussel embryos.” The Final 2014 Shelter Island Yacht Basin Dissolved Copper TMDL Monitoring and Progress Report, prepared by AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Inc., findings: “Consistent with the 2013 monitoring event, the 2014 results indicate that only one station (SIYB-1, the station farthest inside the basin) had a statistically significant effect on developing mussel larvae.”

RCW Chapter 70.300

The full text and history of RCW Chapter 70.300, which was originally written as Senate Bill 5436, modified as Substitute Senate Bill 5436, and amended by the House, can be found online at .https://leg.wa.gov

Washington State’s notice on the existing ban’s delay can be read online at https://ecology.wa.gov/Waste-Toxics/Reducing-toxic-chemicals/Washingtons-toxics-in-products-laws.

Questions pertaining the proposed legislation, the existing ban (and the delay), or other related issues can be directed to Kimberly Goetz at (360) 407-6754 or kimberly.goetz@ecy.wa.gov

*This article is an update to the American Coatings Association (ACA) Industry Market Analysis, 9th Edition (2014-2019).

CoatingsTech | Vol. 15, No. 3 | March 2018