By Scott Adams, The Boeing Company

This article will walk through the first and often the most complex part of a robotic application setup process, explain practical techniques, define some basic process acceptance criteria, and define typical terminology used by some of the industry’s most capable paint application specialists.

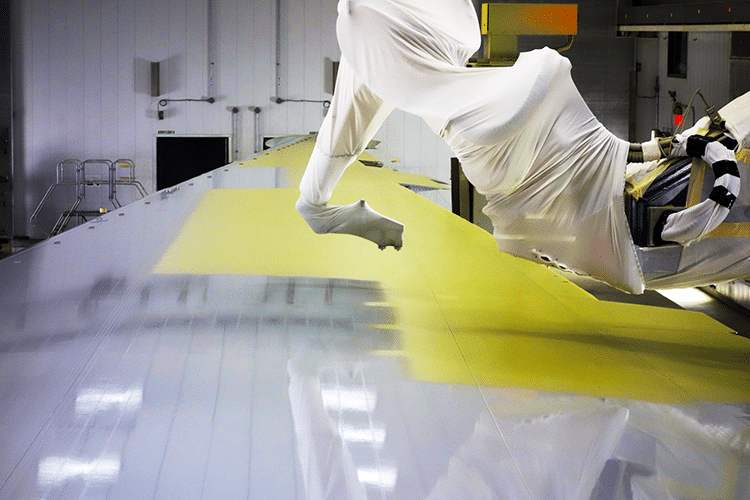

Adding a painting robot to a production process can bring with it improved quality and productivity. The functionality and cost of robotic paint systems has improved tremendously over the past two decades, and the technology is earning its way into small and medium-size production operations.

Coating systems bring tremendous value in decorative application and functionality to products. At the same time, the industry goes to great lengths to minimize or eliminate human exposure to overspray and solvent vapors.

For repetitive coating processes, a robot can be a great way to minimize human exposure, provide a stable and uniform film across months and years of production, and maximize production throughput. It is not difficult to program a robot to move along a path at a given speed and trigger a paint applicator nor is it difficult for a human to wave their arms and trigger a spray gun. Knowing how to properly configure the applicator, coordinate triggers and motions, and manage process variables is what separates a highly skilled painter from an unskilled sprayer.

There can be a dozen or more interrelated factors at play during a coating application process. What seems simple on the surface has left many capable engineers and chemists wringing their hands in frustration while spraying hundreds or even thousands of test panels to find optimal application settings for their robotic application process.

A trial-and-error setup approach is expensive, time consuming, and frustrating for everyone involved. Fortunately, there is a very successful and time-tested structured methodology employed by many of the coating industry’s most capable users, applicator manufacturers, robot manufacturers, and material formulators.

With a data-driven and structured approach, any organization with a robot and a paint applicator can leverage these techniques to greatly reduce the time and effort required to set up a high-quality robotic painting process. There is a wealth of technical literature available on paint atomization, coating formulation, and robotic optimization.

A person new to this rapidly growing field of automated paint application may find themselves overwhelmed with data or may not realize that they are reinventing wheels that were perfected long ago.

This article will walk through the first and often the most complex part of a robotic application setup process, explain practical techniques, define some basic process acceptance criteria, and define typical terminology used by some of the industry’s most capable paint application specialists.

APPLICATION PROCESS OVERVIEW

A successful robotic paint application plan is rooted in well-informed choices, trials and tests that revise or confirm those choices, and an approach that successively builds complex processes with confirmed data. It is nearly impossible to “guess and check” robot path and applicator parameters that will result in a stable quality coating without wasting significant time and material.

Another approach often doomed to failure involves creating an “efficient” path for the robot and then attempting, usually for weeks or months, to find applicator parameters that meet the requirements of the robot path. An analogy of trying to install the roof of a house before the foundation is poured comes to mind. A systematic setup process can be performed on relatively inexpensive metal coupons and masking paper that will save a tremendous amount of time, expense, rework, and headaches.

The steps outlined in Figure 1 illustrate the process. Avoid the urge to skip steps in the interest of time, money, or professional ego. If the assumptions are correct, the test will be quick, easy, and use minimal resources. If the assumption is incorrect and not realized at the proper stage, all the downstream steps will be wasted effort and will need to be repeated. Each of these tasks will be described with the general criteria for acceptance before moving on to the next step.